TOPIC 5.2 “Manifest Destiny”

The election of 1844: What Should an Abolitionist DO?

Unit 5: Learning Objective B - Explain the causes and effects of westward expansion from 1844 to 1877.

Objectives: Students will analyze the political and moral dilemmas faced by abolitionists during the election of 1844 and explore the tension between moral clarity and political compromise in social justice movements.

“(Whigs and Democrats are) only differing… in name. They are of one heart, one mind…Both hate negroes, both hate progress...and upon this hateful basis they are forming a union of hatred.” - Frederick Douglass

“Why support the Liberty Party? Because the existing prominent parties cannot be supported without moral wrong.” - Liberty Party pamphlet

“But what can Berney (sic) do? The most that the abolitionists can do, is to give him the electoral vote of Massachusetts. They can carry no other state…so voting for Berney gets you both Polk and Texas.” - Abolitionist Newspaper, October 1844

“Level Lessons”

This is a “Level Lesson,” a dynamic and engaging way to break down complex historical topics. It ensures that every student follows along at each stage of the activity. This style of lesson allows us to engage students by being the “Guide on the Side” rather than the “Sage on the Stage.”

Short Description:

Students work in groups and progress through a series of “levels,” analyzing one document at a time. They can only advance after passing a quick verbal quiz, ensuring everyone comprehends the material before moving on. This method provides immediate feedback and significantly enhances post-activity discussions, as all students are prepared and engaged.

(Download the full description of a “Level Lesson” above).

Lesson Plan

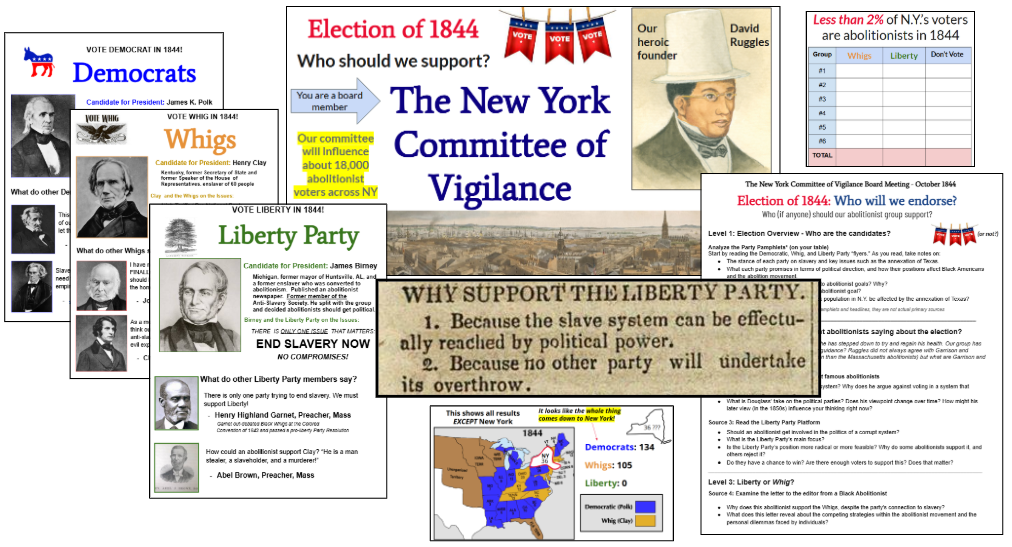

Divide students into six groups, each representing a regional Board of the New York Committee of Vigilance. The year is late October 1844, and our leader, the great abolitionist leader David Ruggles is unwell. Each regional board must decide for themselves whom to endorse in the crucial upcoming Presidential election.

Context (8-10 minutes): Using the slides #2-9, provide context for the lesson. Students need to know about the Texas Revolution and the potential for annexation, and its consequences.

Students also need to be introduced to David Ruggles (Click here for the link) and his multi-racial team of superheroes known as the New York Committee of Vigilance.

Level Lesson (20-25 minutes): All six groups through the three document-based levels and into the “level 4” discussion. Some groups will get more time to discuss than others.

Level 1: Election Overview - Democrat, Whig, and Liberty platforms

Level 2: Quotes from William Lloyd Garrison, Frederick Douglass, and a Liberty Party primary source

Level 3: Abolitionist newspaper arguing for the free Black population to vote Whig

Level 4: Group Discussion

I have slide #11 (party pamphlets) displayed during most of the level lesson, and then switch to slide #12 when most groups are discussing their final decision.

Vote Tally (5-8 minutes):

Each group appoints a speaker to present their decision on how to advise the 3,000 abolitionists in their region. Groups can split their endorsements if there’s internal disagreement. Record their votes on the whiteboard (slide #12)..

Dramatic Reveal, the 1844 Election Results (5 minutes): I start by showing students slide #14 which is the national results minus the state of New York. I let them ponder that in silence for a few moments before pointing out that the entire election will come down to the state of New York and its 36 Electoral College votes.

Then we move to slide #16 to look at the totals in the State of New York. First, I remind them of the totals of our endorsements. Then, for as much drama as possible, I reveal the totals for each party adding our endorsements to the totals to make a grand total for each Party.

If just two out of the six groups endorsed the Whigs (which would equal 6,000 votes), they will change history because the Whigs lost New York, and therefore the election by only 5,000 votes.

I have done this lesson a few different ways but each time, at some point, a Whig supporter is going to blame Liberty Party supporters for the annexation of Texas. This is a moment to grab on to as it leads to a powerful final discussion.

The Effects: (3 minutes). Slides #20-25 briefly describe the effects of the election and the annexation of Texas, focusing on the more than 180,000 people who will be trafficked to Texas, a place that had previously abolished slavery, as well as the fact that New York’s free Black population will decline by over a thousand as the city becomes less safe for their communities, especially after the passage of the Fugitive Slave Act.

Final Class Discussion (10-15 minutes): Make sure to save at least 10 minutes for this. The discussion was so great this year that I might extend it into the following class next year and turn these questions into a Dave Stuart-style pop-up debate.

Should abolitionists focus more on staying true to their core moral beliefs, or is it more important to take action in the political system to make change?

What does the election of 1844 reveal about the unintended consequences of prioritizing moral clarity over political compromise? How did abolitionist leaders like Garrison, Douglass, Henry Highland Garnet, and members of the Liberty Party differ in their approaches to politics during this time? What can their disagreements teach us about the challenges and tensions within movements for social change?

Does the dilemma abolitionists faced in 1844 still apply today? Are there examples today where social justice movements must decide whether to work within the political system or reject it because it goes against their values?

To what extent are New York abolitionists responsible for the consequences of the 1844 election, such as the spread of human trafficking to Texas?

Printing Instructions:

pg. 1-3: One-sided, 12 copies each.. Give each group 2 of each pamphlet to start.

pg 4-5: Back-to-Back. - This is station #2. print 1 for each student.

pg 6: One-sided: Station #3, print 1 for each student.

pg 7-8: Back-to-Back. Print 1 for each student. Hand these to students at the very start of class.

A Note on Historical Accuracy and the Justification for Creative Liberties

The ultimate goal of social studies is to empower students to become critically engaged citizens. Lessons like this help students think deeply about how to engage in society, navigate complex ethical and political decisions, and contribute to building healthier, more inclusive communities. The discussion at the end is especially important, as it challenges students to reflect on their own values and strategies for creating change, drawing essential connections between historical events and their own modern civic responsibilities.

This lesson takes some historical liberties for the sake of engagement and deeper discussion. I wanted to choose a group of New York abolitionists because even though they were in the extreme minority in their state, in this election, they had the power to sway the entire national election. I chose the New York Committee of Vigilance because they were a group of superheroes that almost every student will have never heard of. While the New York Committee of Vigilance did not play a direct role in endorsing candidates during the 1844 election, its inclusion in the lesson serves a powerful purpose. The Committee, under the leadership of David Ruggles, was an essential organization in the fight against slavery and injustice. Ruggles was an abolitionist, journalist, and Underground Railroad conductor whose work deserves greater recognition in our classrooms. By centering this lesson around a fictionalized fractured vigilance committee, students are not only introduced to Ruggles' legacy but also engage with the broader tensions and dilemmas abolitionists faced during this pivotal election.

The election of 1844 in New York highlights the unintended consequences that can arise when those fighting for human rights are unable to unite or compromise. This moment in history provides an invaluable case study for understanding how fractured movements can sometimes lead to worse outcomes, even when each faction is driven by deeply held moral convictions. By using regional newsletters as a narrative device, the lesson fosters a dynamic and engaging classroom environment. It encourages students to grapple with the real-life challenges of political strategy versus moral clarity—a dilemma that remains relevant in social justice movements today.