Antiracist APUSH began as an effort to make AP U.S. History more truthful and inclusive by connecting the world of modern historical scholarship to high school classrooms. That work has been well received and has broadened its scope over the last few years. Today, I am excited to announce that Antiracist APUSH will now be called Empowering Histories.

The Antiracist APUSH project began in 2017 while I was completing my graduate research in the field of Black political history. It was clear that I needed to update the classroom material I was providing to my own AP U.S. History students. A shameful gap still exists between what professional historians have proven and what gets printed in state standards regarding issues of race, slavery, and injustice. The gap between the truth and the curriculum is unacceptable.

In 2019, I was encouraged to expand my mission to support other teachers in this work. The primary objective was to help students identify and confront the racist policies that have contributed to racial disparities in American society. By exposing students to the research of leading historians, they gain a more complete understanding of the injustices embedded in American institutions. As educators, we bear the crucial responsibility of confronting racism and its legacies, ensuring that all voices are heard and valued in our narrative of the past.

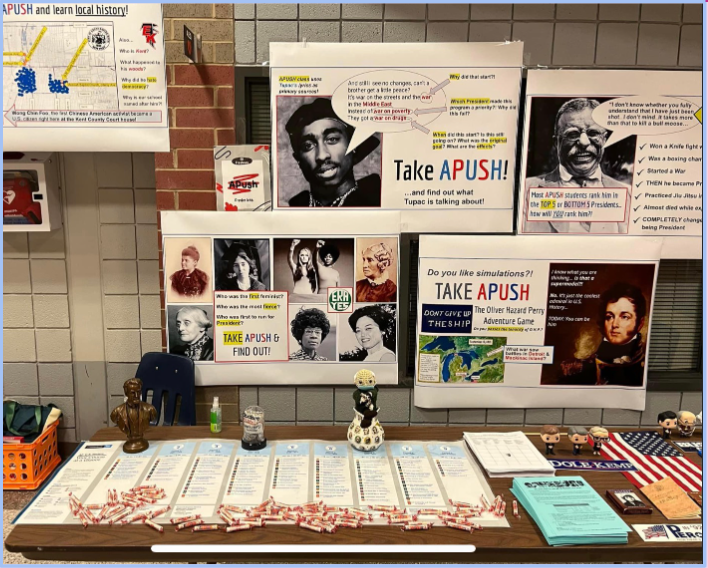

In 2023, my experience as a pilot teacher for the new AP African American Studies course prompted an expansion of the materials offered on this website. It became clear that the original name no longer captured the full breadth of our mission. This idea emerged from a powerful moment at a recent Michigan Department of Education Board meeting. I was asked to bring some of my students to discuss our antiracist approach to U.S. History and our experiences in the AP African American Studies pilot. As my students took the stage, their focus was more expansive than just confronting racism. They took their moment in the spotlight to celebrate empowerment. One of my senior leaders articulated this perfectly, stating, “When you finally learn your history, you are truly liberated…this encapsulates how I truly feel about taking the AP African American Studies class.”

This new name better reflects the essence of our mission: it goes beyond simply “calling out” or addressing racist language and myths; it’s about "calling people in" and providing a more honest and accurate context for our society that is necessary for meaningful change. This work goes beyond revising racist history books; it is more than academic. It’s about reshaping how we interact in the world and engage with our communities. There’s so much at stake—this work touches on our humanity and our capacity to assist in ushering in a more equitable society. “Empowering Histories” represents an open invitation to all of our students to be a part of this process.

The name “Empowering Histories” also reflects our commitment to inspire appreciation for the resilience, creativity, and contributions of diverse communities throughout our history. This makes history education more engaging and meaningful for every learner. A student encapsulated this perfectly during a recent Socratic seminar on the Middle Passage when describing the emotion she felt during a silent gallery walk focused on the Middle Passage and artists' attempts to reclaim the imagery, memory, and emotion of tragedy. The word she chose to describe her reaction was powerful. She explained it this way, “I couldn’t stop thinking about how this had to be one of the most intense efforts to try and take away people’s humanity, but it still didn’t work. No matter what the enslavers tried to do to turn humans into objects, it didn’t work. They found ways to keep their culture and made a new one by surviving and blending their cultures together, and that is my culture, and it makes me feel like I can do anything.”

Empowering Histories is about so much more than just dispelling misconceptions about the past. When students are “called in,” they also become equipped with the knowledge and confidence to recognize their agency as change-makers in their communities. Through this work, we invite all students into the vision and mandate of Langston Hughes: “Oh, let America be America again, the land that has never been yet, and yet must be, the land where everyone is free.”

Continuing the Work:

Despite the name change, the core mission of the website remains the same: to provide high-quality, research-based educational resources that help teachers and students confront and understand the complexities of history. The site will continue to offer print-ready lessons, plans, answer keys, and slides that make teaching diverse histories effective and impactful.

The purpose of Empowering Histories is to engage students in the pursuit of a more equitable future, encouraging them to be part of the generation that brings this country closer to its originally stated founding values. This is accomplished by providing materials that enhance teachers' confidence in delivering instruction and creating spaces for reflection and dialogue that build stronger, more informed communities. Through this work, we strive for an inclusive America where everyone is empowered to realize their potential and free to thrive.

STEPS TO CREATE AN EMPOWERING AND ANTIRACIST HISTORY CLASS

#1 Acknowledge that race is not real, but racism is. Recognize that while race lacks a biological basis, racist policies have profoundly shaped the development of American institutions and continue to impact society.

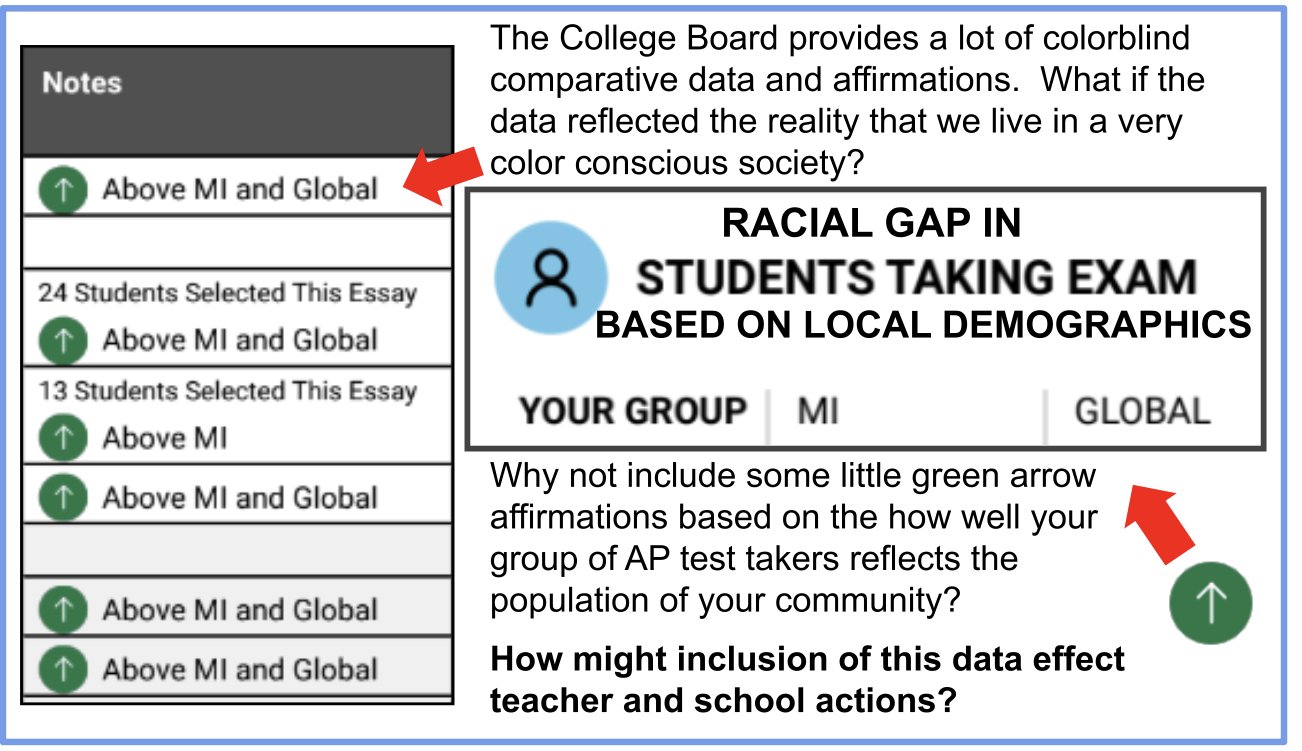

#2 Identify and challenge discriminatory policies. Address the structures that perpetuate racism and challenge history textbooks and state standards that do not accurately reflect the influence of racist policies.

#3 Celebrate the resilience and contributions of diverse communities. Create an inclusive environment that values and elevates all voices, affirming students' identities and experiences.

#4 Maintain high expectations for all students. A quality education is a civil right. Appreciate different communication styles and forms of expression.

#5 Empower students to be change makers. Encourage critical thinking, reflection, and open dialogue about race, history, and justice. This is the foundation necessary to sustain our democracy and modern civilization. Help students realize their agency in creating a more equitable and perfect union, one where everyone is free, not just to survive, but to thrive.