2.2-2.4 The Transatlantic Slave Trade and Resistance on the Middle Passage

“Literary Archeology”: processing the Middle Passage

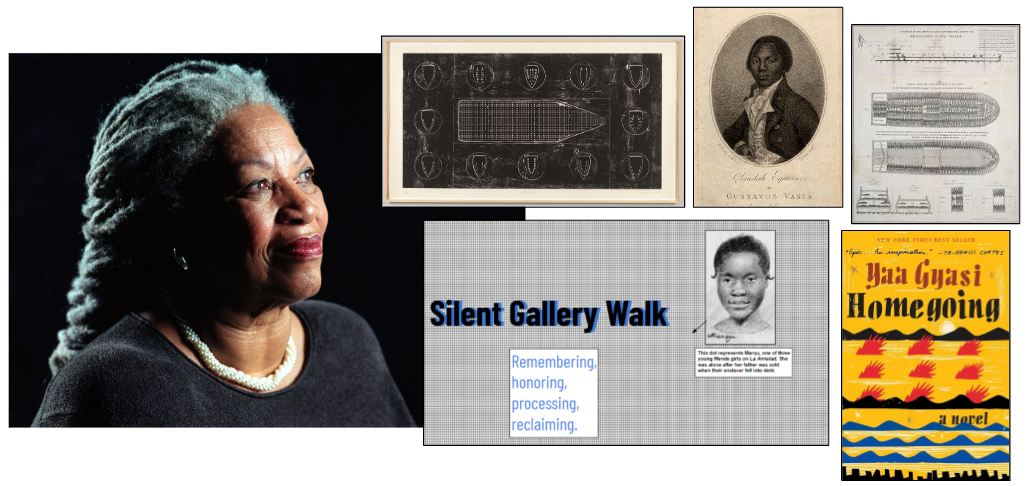

Three Day Activity: SILENT GALLERY WALK and SOCRATIC SEMINAR

LO 1.8.A - Describe the function and importance of Great Zimbabwe’s stone architecture.

Objective 1: Students will evaluate how artistic expressions and literary works (e.g., Willie Cole’s Stowage, Yaa Gyasi’s Homegoing) convey truths about the emotional and psychological experiences of the Middle Passage and slavery in ways that complement historical data.

Objective 2: Students will be able to describe the size and scope of the transatlantic slave trade and experiences of the Middle Passage

Objective 3: Students will be able to describe resistance to transatlantic slave trade and the Middle Passage

“No slave society in the history of the world wrote more…about its own enslavement….But…popular taste discouraged the writers from dwelling too long or too carefully on the more sordid details of their experience…Over and over, the writers pull the narrative up short with a phrase such as, "But let us drop a veil over these proceedings too terrible to relate." In shaping the experience to make it palatable (to white readers)…My job becomes how to rip that veil drawn over "proceedings too terrible to relate." The exercise is also critical for any person who is black, or who belongs to any marginalized category, for, historically, we were seldom invited to participate in the discourse even when we were its topic. Moving that veil aside requires, therefore, certain things…memories and recollections won't give me total access to the unwritten interior life of these people. Only the act of the imagination can help me….How I gain access to that interior life is what drives me and… It's a kind of literary archeology: On the basis of some information and a little bit of guesswork, you…reconstruct the world that (the sources) imply…Therefore the crucial distinction for me is not the difference between fact and fiction, but the distinction between fact and truth. Because facts can exist without human intelligence, but truth cannot. So if I'm looking to find and expose a truth about the interior life of people who didn't write it (which doesn't mean that they didn't have it);… I'm trying to fill in the blanks that the slave narratives left - to part the veil that was so frequently drawn…” - Toni Morrison, “The Site of Memory in Inventing the Truth: The Art and Craft of Memoir”

(As a history teacher brought into the “interdisciplinary world” of AP African American studies. No other text or College Board PD better helped me understand the importance and necessity of an interdisciplinary approach, than this brilliant essay from Toni Morrison)

Notes

Understanding the Middle Passage and the experience of enslavement requires more than the analysis of primary sources can offer. The content covered in the first few sections of Unit 2 is precisely why African American Studies requires an interdisciplinary approach. As the Toni Morrison quote above explains, the context in which slave narratives were written means that while they are eloquent and contain important facts, they are incapable of telling the entire truth of the experience. This is why the work of modern artists such as Willie Cole is a required source.

This silent gallery walk and Socratic seminar discussion lead to some of the most powerful moments in my classroom during the first semester. The sources include many required materials for topics 2.2-2.4.

This will take 3 to 4 days to complete, but it covers enough required content to keep you on track with the course pacing.

**EVERYTHING YOU NEED IS HERE EXCEPT THE EXCERPT FROM HOMEGOING**

If you don’t have the book, buy it! Or get it from your library. There is a good chance, (if your school has any educational credibility) that there is already a copy somewhere in your building! I use the first four pages of the “Esi” chapter. In the 2017 First Vintage Books edition (an orange-covered paperback) this passage is found on pages 28-31, starting with the beginning of the chapter: “The smell was unbearable” to “the other warriors knew the forest better than they knew the line of their own palms. And this was good.”).

SETTING UP THE GALLERY WALK THE DAY BEFORE

The class before the Gallery Walk: I introduce the Gallery Walk and Socratic Seminar at the end of the lesson the day before. I tell students that we are going to start the Socratic seminar practice with a gallery walk the next day, and we will eventually get to this question:

“Is it possible that Marvel’s Black Panther contains more truth than our school’s AP US History textbook?” (Slide #1 of the slide deck)

Students find that question intriguing and hopefully will have some initial inquiries about what the question means. I like to let that ruminate for the evening.

Preparation before class on Gallery Walk Day: Print out the materials. Yes…it is 280 pages. I got permission ahead of time to use hallway space, and it took me and six students two hours to tape it up in the hallways. You can reduce the number to as low as 40 pages if you don’t have full support from administration or student help. That being said, for me, and given the weight of this content, the full printing and prep time was worth it.

Lesson Description: Day #1 - Silent Gallery Walk

Hand out the Socratic Seminar Packet to students (I actually make it available a day earlier for students who want to look it over beforehand, but that is not necessary). The packet contains the questions and necessary readings for the lesson. Class starts, and I introduce the lesson and briefly preview the Socratic Seminar that will begin on Day #3; however, don’t spend too much time on those details. Day #2 is designed to explain the seminar and prepare. Day #1 is about reflection and processing.

Slides 2-6: Use these slides to explain that we will be having a Socratic Seminar in a few days based on this content. Today, we won’t worry about the details of exactly how that will work; instead, we will focus on processing the realities of the Middle Passage. Slide #5 has a few “best practice” reminders to explain to students as we dive into the topic of slavery. These come from Dr. Hasan Kwame Jeffries’ excellent podcast on teaching slavery, Teaching Hard History. I use slide #6 to explain that we will continue our class routines for this topic (i.e., vocab, Must Knows, texts); however, this content requires us to dive in on a deeper, more human level to better understand it. This topic is exactly why APAFAM requires an interdisciplinary approach. We will also use the work of modern artists and reflect on our own emotions to get a more accurate picture of this historical event.

Description of the Emotions Wheel: In reality, I thought I would get more student pushback on this aspect of the activity (i.e., what does the emotions wheel have to do with understanding a primary source?). With slides 8 and 9, I explain why this is included. First, I tell them that emotions are like the weather—we can’t pick them; they just happen. But reflecting on emotions can be an important tool. Emotions stirred by reflecting on the Middle Passage can deepen your understanding of history and humanity and inspire responses rooted in empathy and justice. During the activity, students are prompted to capture their immediate thoughts and feelings. I tell them: “Don’t overthink it. I just want you to get words out on the page.” This is page 3 of the Socratic Seminar packet and the only required writing for Day #1.

I display slide #10 to launch them into the activity.

The silence begins in class as students are instructed to read two documents. The first is a passage from Ottobah Cugoano’s narrative, published in 1787. The second is the first four pages from the “Esi” chapter of Yaa Gyasi’s 2016 novel, Homegoing (in the “2017 First Vintage Books edition,” orange-covered paperback, this is pages 28-31, starting with the beginning of the chapter: “The smell was unbearable” to “the other warriors knew the forest better than they knew the line of their own palms. And this was good.”).

**Homegoing is the only source that you will need to obtain on your own!**

When students are finished reading, they may start reflecting on their emotions, or they may get up and start the gallery walk. The gallery walk is based on the visual of 50,000 dots per page that I include in my Unit 2 vocabulary packet. Students will walk past 250 pages of dots that represent 12.5 million people forced to endure the Middle Passage. In between, students will read Equiano’s account of the Middle Passage, a historical marker on the Igbo Landing revolt, and the 1807 diagram of the Brooks slave ship. When students return to the room, encourage them to stay silent and write more on the emotional reflection page.

When the majority of the class returns, I will display slide #12 on the board showing Willie Cole’s “Stowage” print. I ask them to look and think: What do you see in this modern art print? What is this? Why would someone make this?

In the last 5 minutes of class, I ask for volunteers to describe what they see in the print. After a few students share, I show slide #13 and briefly describe Willie Cole’s background and art. Cole is a visual artist from New Jersey. As a young man, he was exposed to the Black Arts Movement and education on African history and culture. One day, he saw an old iron in the street and originally saw its resemblance to a mask from the Dan tribe in West Africa. As he looked at the piece and gathered other irons, he saw how they all had similar yet unique markings, and he saw further connections to Black history as the women in his family had become domestic servants after the Civil War. Eventually, he began to see connections to the Brooks ship diagram as well.

Then I direct students to page 4 of the handout and have them briefly reflect on questions 1 and 2.

Homework: Read Toni Morrison’s Essay (pgs. 8 and 9).

Day 2: Work Day and Socratic Seminar Prep

I start the day by showing the Willie Cole print again and have students share their responses to questions 1 and 2 with their tablemates. Slide #14 has the day’s learning targets. I give students the chance to ask questions about Morrison’s essay. Students have the rest of the day to work on the required questions on pages 5-11. Page 5 is the heart of the assignment for the seminar. Students will also be making up two questions of their own.

Day 3: The Socratic Seminar

Students should fold their packets to page 5 and hand them in to the center table. The center table should have six desks or seats. I sit in one of them. The other seats are “first come, first serve.” All students are required to participate. They can’t enter the circle without their packets being complete. This supports my seminar norm of actively listening. I don’t want students working on their packets during the seminar. Students should pick up a half-sheet that has the questions on it so they can follow along.

Students may grab their packet from the hand-in stack while they are at the center table.

My goal is to stay out of the seminar as much as possible. Students must bring up a topic to discuss or ask a question, and also comment on another student’s topic or question. When they have done both of these and backed up their response with evidence from one of the seminar sources, I excuse them and their seat opens. Each student is in the circle for about 5 to 10 minutes. It takes me one and a half classes to get through my classes, which have about 30 students.

Every once in a while, I ask a student from the outer circle to throw in a question or ask them to comment on a question being discussed in the inner circle.